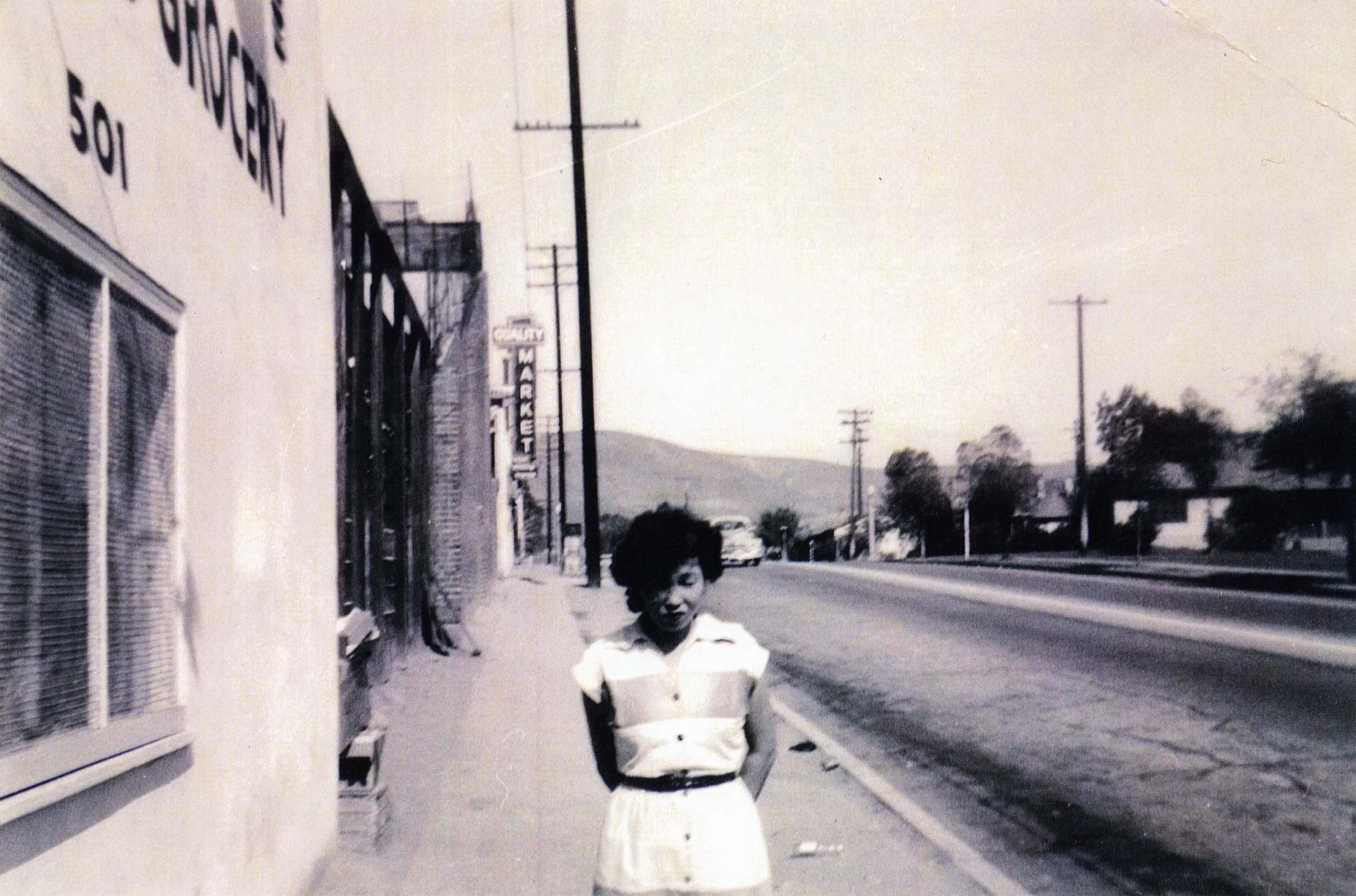

501 N Mednik

501 N Mednik

Every day, the Davidson Company produced 120,000 building tiles and 320,000 sand-molded common bricks from a gaping quarry dug into the hills that separated Monterey Park from the rural settlements of unincorporated East Los Angeles. The brown shale and soft red clay they extracted had been in the ground above Floral Drive for seven million years. The bricks were used in post offices, shopping plazas, and park walls across Los Angeles and adjacent counties. Each one was stamped DAVIDSON.

The downtown real estate rush of the 1920s eliminated the original varrio of Sonoratown and Mexicans were pushed away from L.A. city center. Assimilated Chicanos carved out space for themselves within Boyle Heights’ jumble of Russian Jews, Japanese, Italians, Molokans, Armenians, and African-Americans. Those fresh from La Tusa (Tucson), Juaritos (Juarez), and El Chuco (El Paso) went further and landed beyond the city line, where lots were cheaper and building codes looser. Along Brooklyn Avenue east of Indiana Street a culture of puro Mexicanismo found room to flourish.

A new varrio spread outward from the intersection of Brooklyn and Ford, below the brickyard. East of Mednik Avenue, the neighborhood turned to open fields where Japanese women in bonnets tended to beds of sugar beets, cabbage, and chrysanthemum. In hopes of attracting upwardly mobile Anglos, real estate opportunists branded the area “Belvedere Gardens.” Those who arrived never called it anything but Maravilla. There were no water pipes, sewer lines, sidewalks, drains, parks, or pavement, but they had a handball court.

Locals later boasted that their fathers and uncles smuggled out Davidson bricks two at a time to build the court at the corner of Hammel and Mednik, where two walls met in an L, 20’ wide by 40’ long. They imported the El Paso game to Maravilla: rebote a mano con pelota dura. The rules were viciously simple. Someone served above a guideline on the fronton; the first player to make it impossible for his opponent to return the ball got a point. They played to 12 in best-of-five sets. The only equipment was the wall and a ball, slightly smaller than a baseball but equally hard. They were made to order from an old man on Valley and Muscatel, in South San Gabriel. He eviscerated golf balls and wrapped the salvaged rubber in yarn. A strip of tanned goatskin was stitched around the exterior, then soaked in blue-black ink and left to dry in the sun. If you didn’t learn how to hit it properly, it could ruin your hand. Permit your alertness to lapse for a second and it could split your eye socket and ruin you altogether.

During the war, the government built the Maravilla Public Housing Project on the fields across Mednik, bringing new business to El Centro Grocery, the little market next to the rebote court. In 1947, Shigeru “Tommy” Nishiyama and Michiye Hada took over operations of the store, which connected to the living room of their 600-square-foot house through a small step-down doorway. Both were born in Washington State to families that had returned them to Japan for schooling. They escaped Hirohito’s regime as teenage students, immigrating to Seattle before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Colorado was the only western state that offered asylum to Japanese-Americans in the form of farm labor. While harvesting crops in Rocky Ford, Tommy lost his left arm to a mechanical corn picker. Such were the risks chosen over internment. Michi was 17 when her family was relocated to a camp on the cold desert plains of southern Idaho. She was among the first admitted to Minidoka in September 1942 and wasn’t released until September 1945. She spent the last years of her youth in tarpaper barracks encircled by barbed wire and guard towers.

When the war ended she found work as a maid in Seattle, where she and Tommy met. Their families shared roots in Wakayama, the lush farming district outside Osaka. 1947 was their last summer in the northwest. That July, they married at the Buddhist Church on Main Street in downtown Seattle. Michi wore a satin dress with a scalloped neckline and a trailing silk train. Tommy wore white gloves to hide his prosthetic arm. The following month, they moved to Los Angeles.

After shifts in foundries, factories, and the brickyard, the workingmen of the varrio cracked cans of Brew 102 and Falstaff and wagered on rounds of rebote. Outside, young men with trimmed mustaches dealt Seconals, Tuinals, Nembutals, and marijuana from inside the pockets of their garbardine jackets. The first capsules of Mexican heroin in Los Angeles passed across that sidewalk. Late at night, the brickyard would fire up its massive kilns and kids in their beds pictured a firebreathing dragon prowling the hills.

In a room no bigger than a bus stand, she carried anything and everything a supermarket could offer. Milk, fruit, vegetables, bread, breakfast cereal, bananas, ice cream, canned fruit and beans, toilet paper, cigarettes, soap, Spaghetti-O’s. When her customers had no money, she extended them credit. When they failed to pay a debt, she forgave it. Kids from the varrio peered into her plate-glass candy counter like it was a jewelry case. Instead of making them point to what they wanted, she led them behind the counter and let them reach in and choose for themselves. Inevitably someone would make a pass at the penny candy when she wasn’t looking. If caught, she let them keep what they took and gave them extra for the road. The El Centro sign remained but everyone in Maravilla called it Michi’s.

Each morning Tommy swept the surface of the court clean. Even with one arm, he was a tough player and earned status as an honorary Chicano among the exclusive fraternity of rebote veterans that assembled on afternoons and weekends. There was no lock on the door, but even when it was left ajar, an invisible force seemed to shield the entrance. A boy might enter under the aegis of an uncle or father, but to intrude without invitation was to trample something unwritten. Women, children, and assorted outsiders were left to wonder what happened inside the walls.

While cradling her infant daughter Noriko behind the counter, Michi would send her son, Thomas Jr., to fetch Tommy from the court. The sounds behind the door—guffaws, gruff Spanish, and gunlike thwacks of a game in progress—always made him nervous to knock. The men who answered were such giants that even after Thomas grew up he still couldn’t say for sure whether they’d been good guys or bad. A former four-letter athlete at Garfield High, Chuy Briseno was rumored to have bested #1-ranked tennis player Pancho Gonzales in a pickup match—but his heart belonged to rebote. Chuy had been playing in Maravilla since his father first brought him to the court in the early ‘30s. He could serve while seated on the bench at the back wall and beat the ball to half-court in time to crush his opponent’s best return. By day, he drove grade stakes into the ground for a construction company. “When you meet someone you’ve got to have confidence,” he said as he leaned down to greet Thomas, who would always need a full day to recover from Chuy’s granite-hard handshake.

La Kern; La Marianna; La Ford; La Lopez; La Arizona; La Lomita; El Hoyo. The local cliques loomed large, warring against outsiders of any kind. They fought each other over bragging rights and boundaries, but like siblings with a common father, each gang appended its name with “Maravilla.” It signified fearlessness and independence over everything. No brother, neighbor, or government called shots for a Maravilloso.

In 1951, the Boggs Act established minimum sentences of two-to-five years for any offense related to marijuana, pills, or heroin. After the Narcotics Control Act of 1956, the penalty increased to five-to-ten for simple possession. Newly minted narcs hovered near hotspots: Michigan and Carmelita; Brooklyn and Ford; Hammel and Mednik. The number of Maras in Men’s Central Jail would eventually become so great that the sheriffs tried to curb their influence by segregating them in a special tank named for the neighborhood. Others forged heavyweight reputations in the CDC’s major league: Tracy, Soledad, San Quentin, and Folsom. On every yard, handball was the champion sport.

Mandatory minimums did nothing to prevent heroin from permeating the varrio. Stick-ups and break-ins only increased in the absence of streetwise elders. The County Housing Authority forbade flowerbeds in the projects, claiming they were only stash spots for guns and drugs. When sheriffs threatened to condemn the rebote for “code violations,” Tommy, Chuy, and a few reputable old-timers intervened and organized an official club to govern the court. They installed a lock on the door and gave keys only to dues-paying members. The club convened at daybreak on Saturday and some players wouldn’t leave until Sunday night. They bought cases of Eastside Old Tap from Michi and switched on floodlights for the late games. Some took up racquetball and Basques drove from La Puente and Ontario to play their version of pelota, but after 2pm, it was only hardball. All-night games of poker and Pan commenced under a lamp in the converted broom closet they called “the casino.” On Sunday mornings, Tommy would fetch a pot of menudo from Juanito’s on Floral, as bleary gamblers sobbed to Michi about losing a month's pay to a bad hand. She would console them and then gently pass a roll of bills to cover the rent.

When the original projects were razed and rebuilt between 1972 and 1975, half of Michi’s customer base relocated to quieter lives in the East L.A. suburbs: Pico Rivera, Whittier, Hacienda Heights. Weekend beer sales might have saved the business. When their landlord sold the property, Tommy and Michi had enough to buy the lot, the house, and the handball court. From then on, the club covered the light bill and rented the court from Tommy. With the crowd cheering him on, a Basque they called “El Espanol” scaled the bricks like a spider and tied red letters to the fence atop the fronton: MARAVILLA HANDBALL CLUB. At three stories, it was an Empire State Building of the varrio.

Club members continued to meet on the weekends until there was no one left to meet. Pelota dura died with the old-timers. As it turned out, few teens were eager to risk broken hands only to be schooled by their grandpas. Those that didn’t turn to basketball or soccer took up the game in parks using a soft bouncy racquetball known as “big blue.” No self-respecting Maravillioso would even call it handball.

The Maravilla gangs multiplied in the 1980s and Mednik became a combat zone. Stray rounds left scars on the rebote, but like a church, Michi’s remained unscathed. Never robbed, never tagged. Maras in L.A. County Jail would use their one payphone privilege to call the store, knowing Michi would always be there to accept the charges and relay a message to anyone in the varrio. Sometimes she’d be asked to hold a paper bag behind the counter. Her son implored her otherwise. “People think you’re involved,” he said. She shooed him off. The men outside had once peered wide-eyed into her candy counter. They were her customers. “Besides,” she said, “I never look inside.”

The $1 sandwiches she started making for club members were so popular that every day someone would come in for a “Michi sandwich,” though they were never on a menu. In the face of rising costs and supermarket competition, she refused to raise prices. “The people can’t afford that,” she told her son, who later discovered she was supporting the store with her life savings. In a boom year, a Korean developer offered them a million for the lot. Thomas was incredulous when he found out they turned it down. Tommy shrugged. “I’m waiting for two million.” As Michi got older and smaller, the shelves seemed to grow taller around her. The wooden grabber from the ‘30s leaned against towers of cereal that nearly touched the ceiling. She developed painful sores from standing all day. Each day, an aging gangster from Lomita Mara would walk over from the projects to put healing lotion on her aching feet.

After they failed to answer a knock from the neighbor, she and Tommy were found incapacitated on the floor. They'd fallen while trying to help each other stand. In the hospital, the doctor forbade them from returning to Hammel. Thomas enrolled them in KEIRO, where elderly Japanese rode stationery bikes and ate salmon teriyaki and kazuzuke at lunch. Michi stayed in Boyle Heights while Tommy went to Gardena. After a few months apart, a two-person vacancy opened, but Michi lapsed into a coma before they could move her. She was gone by the time Tommy reached her bedside. He put her hand in his and wept as the family closed the door behind them.

After the funeral, he told Thomas to take him to Maravilla. He was embraced as soon he stepped on the sidewalk. When his son came to pick him up, Tommy refused to get in the car. They argued but all Thomas could say was: “Just don’t go in the store.” The following weekend he returned to find spoiled milk in the coolers and produce rotting on the shelves. “I saw your mother last night,” Tommy said. His son threw everything away and shut off the electricity. “Leave it,” he said. He’d return each weekend in the months before Tommy passed, always to find the door open, the lights on, the shelves full.

Upon returning from 15 or 20 years in Susanville or San Quentin, a Maravilloso would make a stop on the sidewalk outside the rebote, where the most seasoned and reputable figures from La Kern, La Lopez, and El Hoyo still met. It was their backyard, their boardroom, their library. They remembered when 17-year-old Joe Morgan from Ford Mara went to jail for killing his older lover’s husband with a hammer; he escaped from County Jail in ‘46 and was shot in the leg by deputies during a standoff at Eugene and Ford. By the 1970s, he was one of California’s most respected convicts, unhampered by his prosthetic leg. Inmates at Chino watched him play handball for hours, hard and silent and alone inside Palm Hall’s encaged exercise yard.

The construction of the Long Beach and Pomona Freeways drove two stakes through the heart of Maravilla. La Kern and La Ford were two of the strongest names in the varrio, but neither could survive the attack from Caltrans. Their veteranos continued to command respect at the rebote. One day, a young gangbanger parked on Mednik and heedlessly pushed aside a short, gray-haired grandfather from Kern, who returned with a machete and decapitated his offender on the spot. Some said that in the ‘50s, one of those heavy hitters from Kern had carried on a long affair with Michi, but that was the kind of thing you’d only hear after long hours in the company of sidewalk historians. They knew everything, except why Michi and Tommy had chosen to settle on the corner of Hammel and Mednik.

The mention of her name alone is enough to make anyone from Maravilla melt. They remember her at end of summer days, pulling her stool onto the sidewalk to sit in the last of the afternoon sun. She’d be seen counseling young women. Many who couldn’t afford a wedding dress were married in Michi’s, which she hung in the back of a closet in the tiny house. Privately they called her La Madre de Maravilla. Some time ago, an OG from Maravilla arrived fresh on the yard at Pelican Bay, the new supermax prison on the Oregon border where Joe Morgan spent his last years. Strangers crowded him and sized up his tattoos. “You’re from Maravilla?” He was 800 miles from home and said yes only after bracing himself. “Órale!” said his interrogator. “You ever had a Michi sandwich?”

In the ‘90s, Los Angeles razed almost every one of its handball courts during a wave of gang panic. Maravilla is now the oldest by far. Decades of weather have split the wood and gnarled the cushions of the benches along the back wall. In the far corner, a plywood placard lists the names of club members in hand-lettered script: GALLEGOS; ESQUIBEL; NISHIYAMA. Some of the best were known only by nickname: PALOMINO; CONEJO; SCOPETA. On the other side of the wall is another set of names, barely visible beneath layers of peeling coverup, each carved into the surface of a decaying Davidson brick: JUAN HMV; RUDY LMV; RAY; KIKI; HAWK. The grocery is shuttered and padlocked, but Michi’s counter is still inside, centered in the darkened room, surrounded by empty shelves.